Natural Mystic

Throughout her life Brazilian singer-songwriter Joyce fought against blacklists and being sidelined from here own projects to represent her true self in her songs. Lost 1977 Joyce album with Mauricio Maestro and legendary producer Claus Ogerman released for the first time.

Not long after the dawn of her career, as a teenager in Rio de Janeiro, Joyce was declared “one of the greatest singers” by Antonio Carlos Jobim. Yet despite reputable accolades and the fact that she has since recorded over thirty acclaimed albums, Joyce never quite achieved the international recognition of the likes of Jobim, João Gilberto and Sergio Mendes, all of whom became global stars after releasing with major labels in the US.

There was a moment when it seemed Joyce might be on the cusp of an international breakthrough. While living in New York, she was approached by the great German producer Claus Ogerman. Ogerman had already played a pivotal role in the development and popularisation of Brazilian music in the 1960s, recording with some of the all-time greats like Jobim and João Gilberto, as well as North American idols like Frank Sinatra, Billie Holiday and Bill Evans.

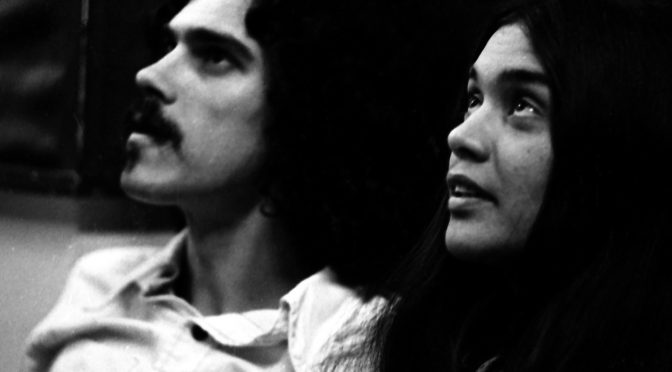

“I met him in New York City, in 1977”, recalls Joyce. “I was living and playing there, and João Palma, Brazilian drummer who used to play with Jobim, introduced me to Claus. We had an audition, he liked what we were doing and decided to produce an album with us.”

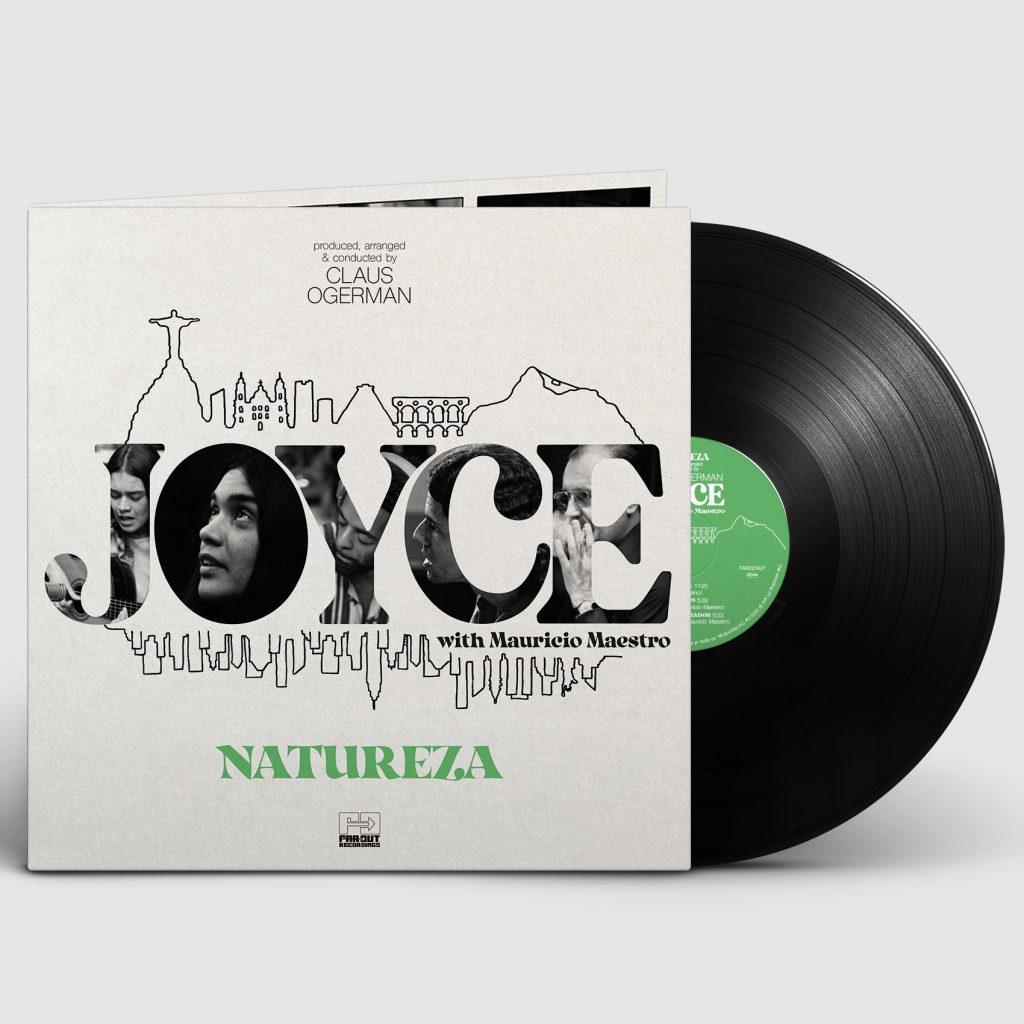

Featuring fellow Brazilian musicians Mauricio Maestro (who wrote/co-wrote four of the songs), Nana Vasconcelos and Tutty Moreno, and some of the most in-demand stateside players including Michael Brecker, Joe Farrell and Buster Williams, the recordings for Natureza took place at Columbia Studios and Ogerman produced the album, provided the arrangements and conducted the orchestra.

But mysteriously, Natureza was never released, and what should have been Joyce’s big moment never happened. As Joyce remembers, “I returned home, but Claus and I remained in contact, by letters and phone calls. He was very enthusiastic about the album and tried to hook me up with Michael Franks. He wanted me to go back to NYC in order to re-record the vocals in English with new lyrics, which I actually wasn’t too happy about. But then I got pregnant with my third child and could not leave Brazil. And little by little our contact became rare, until I lost track of him completely. And that was it. I never heard from him again.”

While Claus was known to be something of an elusive character, the album’s disappearance might also have been a result of timing. The Brazilian craze was coming to an end, making way for disco and new wave at the end of the seventies, and Ogerman struggled to find a major label interested in a new Brazilian sensation. Additionally, as Joyce mentions, it wasn’t quite finished. Ogerman wanted to add finishing touches to the mix and to record alternative English lyrics for the US and international markets – a critical artistic difference between Joyce and Ogerman.

As the military dictatorship’s grip on Brazil began to subside in the 1980s, Joyce had a handful of hits in her home county, including a tribute to her daughters ‘Clareana’, and the iconic ‘Feminina’ – an intergenerational conversation between mother and daughter about what it means to be a woman. But already a feminist pioneer, these successes were hard fought. Joyce had caused controversy as a nineteen-year-old when she became the first in Brazil to sing from the first-person feminine perspective, and the institutional sexism she faced was worsened by the dictatorship who would often censor her music. Even once the Junta was out of the way, Joyce found herself up against the male-dominated major record companies in Brazil, who sought to dictate her career and sexualise her image, before dropping her for refusing to play along.

A few years after the success of her albums Feminina and Agua E Luz in Brazil, Joyce’s music began to find its way to the UK, Europe and Japan, and Feminina and Aldeia de Ogum became classics on the underground jazz-dance scenes of the mid to late-eighties and early-nineties.

The full-length version of Feminina from the Natureza sessions was first heard on a Brazilian Jazz compilation in 1999 and Descompassadamente was licensed for a CD compiling the work of Claus Ogerman in 2002. Following these, word began to get out about an unreleased Joyce album with Claus Ogerman and the legend of Natureza grew.

Forty-five years since it was recorded, Natureza finally sees the light of day, as Joyce intended: with her own Portuguese lyrics and vocals. Featuring the fabled 11-minute version of Feminina, as well as the never before heard Coração Sonhador composed and performed by Mauricio Maestro, Natureza’s release is a landmark in Brazilian music history and represents a triumphant, if overdue victory for Joyce as an outspoken female artist who has consistently refused to bow to patriarchal pressure.

TRACKLISTING

A1. Feminina

A2. Mistérios

A3. Coração Sonhador

B1. Moreno

B2. Descompassadamente

B3. Ciclo Da Vida

B4. Pega Leve

Far Out Recordings will release Natureza on December 2th, 2022.